About

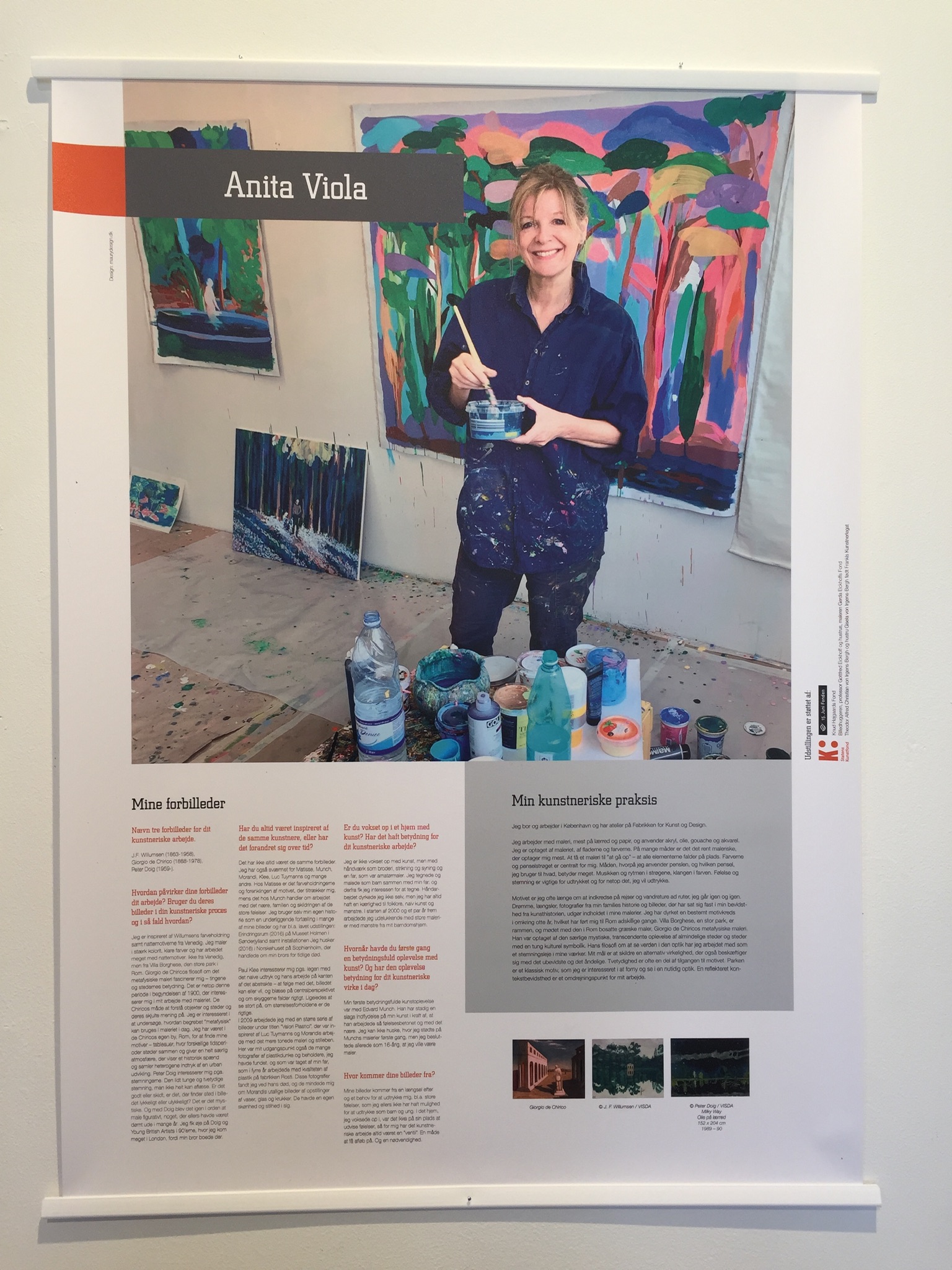

ANITA VIOLA NIELSEN

Wanderings in our inner space is just as real as our meeting with the physical world.

by Jesper Nickelsen

Family photos, urban vistas, wall-paper patterns and flowers: Anita Viola Nielsen’s motifs are to a high degree influenced by objects accessed through the senses, and by places in the real world. But this only superficially so. It is characteristic of Anita Viola Nielsen’s visual universe that her rendering of the physically recognizable is permeated by a strength emanating from the metaphysical sphere. Recollections, memories, intimations, dreams and emotions fuse with street-lamps, plastic containers, parks, and houses in her more or less figurative paintings. One is always on the edge of the real. The properties of reality are being tested and a disquieting (im)balance between inner and outer spaces arises.

Strong colours, dynamic patterns and brilliant surfaces would appear to make Anita’s paintings a source of beauty for the beholder. But though she is indeed in search of beauty, her works are never simply decorative. Below the aesthetically appealing upper surfaces one always finds a story dealing with the human condition, and often about its pains and sufferings: the desperation of existence itself; the grief of losing loved ones; loneliness, melancholia and inner pressures. As an example, take the painting Ravello 2012: On the one hand, a joyous celebration of the fireworks in the night sky above Ravello on the other, a Vanitas-scene and a memorial to her deceased brother. The fireworks are moreover something man-made, a recurring element in Anita Viola Nielsen’s work. We see the traces of the presence of people – a bench , a street-lamp, a sculpture or perhaps a car – but only rarely any actual persons.

Perhaps this expresses a recognizition of the fact that we are always alone with ourselves, and of the loneliness this recognizition entails. Certainly, Anita insists that her paintings are introvert, leaving room only for her own emotions.

Anita’s exploration of what our senses cannot fathom, has the work of Giorgio de Chirico as a major source of artistic inspiration, together with J.F. Willumsen and Giorgio Morandi. De Chirico’s metaphysical period before 1920 has been of special importance for Anita’s mystical and enigmatic pictorial universe. De Chirico and Nielsen both express themselves through a visual language in which the mimetic and logical is displaced by the irrational and disturbing. The iconographical parallels between de Chirico and Nielsen are apparent in a disregard for the realistic perspective, depictions of illogical spatial depths, irrational shadows and the use of personal symbols. The two artists also have a characteristic in common in their dives into childhood memories.

Anita has her most productive artistic periods during her annual stays in Rome: the city in which de Chirico lived and worked for much of his life. Like Athens, Rome attracts Anita in a special way. Both cities span from Antiquity to the Present in a way which brings Anita into contact with a certain primordial state of mind, affecting her both physically and spiritually. She spends many hours on foot, wandering, photographing, seeking out motifs in the urban spaces. This is reflected in her many works from Athens and Rome. Travel to these cities also constitutes an escape from secure, known circumstances, into situations which make her a stranger, vulnerable and alone. In this kind of situation, Nielsens’s senses are sharpened, she finds herself more acutely present in both her inner and in the outer world.

Transforming the intangible into the visual (to the extent possible) has Anita’s highly individual brush technique as a main mediator. Her paintings seem executed with an ease and enjoyment which belies their dependence on a complex exercise of craftmanship.

As a trained graphic designer and with her many years of experience in painting, Anita has developed a personal technique, working almost calligraphically. Her characteristic stroke patterns are achieved by a special, turning, handling of the brush: she ’writes’ with brush, just as poets writing their lines.

The artist’s presence in the world is thus also expressed through the visible traces she leaves on the canvas.

Anita Viola Nielsen

Interview by Helene Johanne Christensen in connection with the exhibition EFTER-BILLEDER. JANUS, Vestjyllands kunstmuseum og SAK kunstbygning Fyn, Denmark 2021

1.Name three artists who have inspired you

J.F. Willumsen (1863-1958), Giorgio de Chirico (1888-1978), Peter Doig (1959-)

How do they affect your work?

Do you use their creations in your own artistic process, and if so, how?

I am inspired by Willumsen’s colour attitude and his nocturnes from Venice. My colouring is strong, using bright colours and have worked a lot with night scenes. Not from Venice, but from Villa Borghese, the great park in Rome. Giorgio de Chirico’s thoughts on metaphysical painting fascinate me – the importance of things and places. It is precisely this period, at the beginning of the 1900s which interests me in my painting: it is De Chirico’s way of understanding the hidden meaning of objects and localities. I want to investigate how the metaphysical may become active today’s painting. To find my motifs I have stayed in de Chirico’s own city, Rome – where different epochs meet, producing a very special atmosphere in which the historical span becomes visible, uniting heterogeneous impressions of urban growth. Peter Doig’s work has my interest because of its moods. That somewhat heavy, ambiguous mood, which one finds it hard to read: is what the image shows us something good or bad, does it have to do with happiness or misery? That’s the mystery. And with Doig, it once again became acceptable to paint figuratively, something that had been looked down on for years. He caught my attention, together with Young British Artists, in the 90s – I visited London regularly then, my brother lived there.

3. Has it always been the same artists who have inspired you, or have there been changes over the years?

There have been changed over time. I have also admired Matisse, Munch, Morandi, Klee, Luc Tuymanns and several others. Matisse’s colour attitudes and stylizations of motifs attract me; with Munch, it is his dealings with the intimate, with family and strong feelings. I often use my own history as an underlying narrative in my images; as in my exhibition Erindringsrum (Spaces of Memory, 2016) at Museet Holmen, Southern Jutland, and my installation Jeg husker (I remember, 2016) in Norskehuset at Sophienholm, about my brother’s all too early death.

Paul Klee’s playing with the naive appeals to me, his work along the borders of the abstract, following the potential, or the will, of the image, rather than caring about the rules of perspective or how shadows are supposed to fall. Or whether relations of size are correct or not.

In 2009, I worked on a major series of paintings entitled Valori Plastici, inspired by Luc Tuymann’s and Morandi’s stilleben paintings. Another point of departure was constituted by the many photographs I had found, of plastic cans and containers, taken by my father. He worked for forty years controlling the quality of the plastic used in the Rosti plant. They reminded me Morandi’s innumerable images of assembled vases, bottles, and jars. They had a certain quiet beauty of their own.

4. Did you grow up in a home with art? Has it influenced you as an artist?

I did not grow up with art, but with crafts such as embroidering, knitting, and sowing – and a father who was an amateur painter. In my childhood, I drew and painted together with my father, from which sprang my interest in graphics. Crafts were not my thing, but I have always had a love of folklore, naive art and patterns. For a couple of years in the early 2000s, I did only large-scale paintings with patterns from the wall-papers in the house where I grew up.

5. When was your first important meeting with art? Does this meeting still influence your work today?

My first decisive experience of art was in the work of Edvard Munch. He still has a kind of influence on my work because of the strong emotions and the in intimacy found in his images. I do not recall when I first saw Munch, but at already at the age of 16 I decided to become a painter.

6. From where do your images come to you?

They come from the longing, the need, I have for expressing myself, not least the strong emotions I did not have the possibility of bringing out as a child and as a young person. Where I grew up, there was no room for showing your feelings. My work as an artist has therefore always been a vent hole, a way of release. And a necessity.